One of the most popular themes running through the mobile phone industry this year has been the unprecedented growth in Android adoption. I’ve argued that the adoption was initiated on the supply side by vendors and operators, but demand has certainly manifested itself.

Android is almost viral in the way it spreads. With no constraints on intellectual property, pricing, contracts, modification or terms of distribution, the incentives to push product out are phenomenal. It even works, mostly.

One hypothesis of the consequences of this viral adoption is that there will be a “commoditization” of smartphones with rapid price erosion to follow. This in turn might even lead to lower margins for Apple and RIM and most major vendors, including those selling Android itself.

In order to test this hypothesis, we need to look at what has been happening to prices. If prices have started tipping down at more than their usual rate then maybe commoditization is happening.

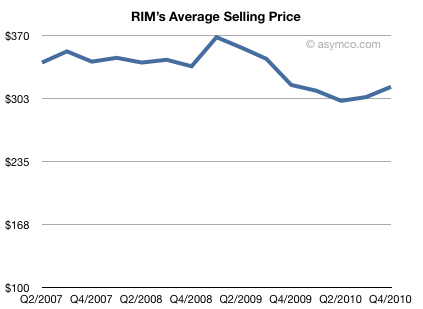

We can begin this test with the industry’s canary in the coal mine: RIM. RIM has been struggling for growth in the very market where Android has been growing the fastest. Is RIM’s pricing under pressure?

Interestingly, no. Their ASP (average selling price) decline, from an average of $350 to $310 in late 2009, came before the Android avalanche. During this year, the ASP has held steady, even rising in the last two quarters to $315 while Android activations reached 300k/day.

So I don’t see a big problem with RIM, yet.

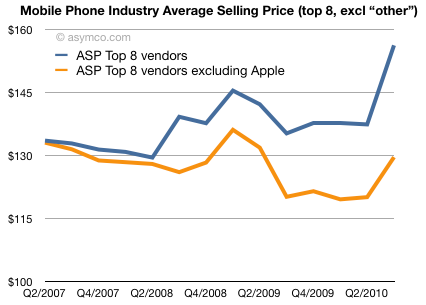

What about the industry as a whole? Can we see patterns that suggest imminent commoditization? Using the top 8 vendors (Nokia, Motorola, Samsung, Sony Ericsson, LG, RIM, Apple and HTC) and using volume-weighted ASP (total device sales divided by total units sold) we have the following chart:

Since the second half of 2007 the “industry ASP” (blue line) has actually increased. This is even though there was a huge recession in the middle of the time period.

This should be only slightly surprising. If you suspected that the iPhone may have a lot to do with that, you would be right. If you remove Apple from the mix, the second line (in orange) shows that the top vendors (ex-Apple) had some, but quite quite mild erosion (from an ASP of $133 to $129)[1].

This is far milder than what’s been happening in the PC sector where prices are dropping catastrophically (According to NPD the average selling price of all Windows portable PCs has fallen from $659 in Oct. 2008 to $519 in Oct. 2009).

So Apple was a big contributor to the industry increasing its pricing power.[2] but even without Apple the industry has been holding on.

But is this just a lull?

Is Android going to stop the growth?

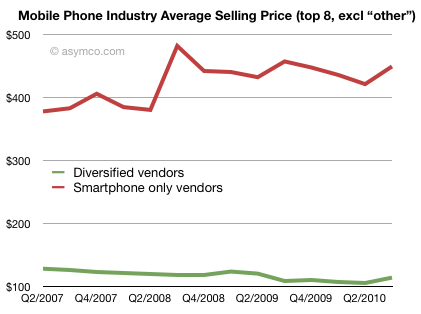

We can look at the pricing data one more way: If we separate the eight companies into two cohorts, the “diversified” vendors who sell both smartphones and regular phones vs. the “pure play” smartphone-only vendors, we get the following price history.

What is happening is that the diversified (Nokia, Samsung, LG, Sony Ericsson, Motorola) saw modest price declines (from $128 to $114) while the pure-players saw price appreciation (from $378 to $449). This is with the early impact of Android priced in. Unfortunately I don’t have a chart showing non-smartphone prices in isolation, but I would be willing to bet it would be a significant negative slope.

In these two lines Android is not an independent variable. Android was adapted by some of the diversified vendors (all but Nokia), but in different ways. The thing is that Motorola and Sony Ericsson had great increases in ASP with Android. Among the pure-play vendors only HTC adopted Android and its performance is undistinguished vs. RIM which didn’t.

So what, if anything, has Android done to pricing?

I argue that there is no evidence in the pricing data of a coming commoditization of smartphones. Android vendors were able to use the platform to move to higher pricing and the more they switched their portfolio to Android the more they got a better average price. At the same time those vendors who built smartphones without Android also saw strong price supports.

The only correlation with pricing power is whether you build smartphones or dumb phones. The more smartphones you build, the more price you can charge. This is regardless of platform.

The reason for this is that the smartphone market is growing so rapidly (90% y/y). There is limited direct competition between smartphones and a lot of competition between non-smartphones and smartphones–a battle smartphones are winning handily, irrespective of price. Smartphones seem to be what everyone wants.

So the real question that should be asked is:

Why do vendors bother making any dumb phones at all?

If you look at the third chart above you can see how attractive it must be for the diversified vendors to abandon the non-smart market to ZTE, Huawei et. al. Perhaps Nokia can still make a small profit there but to do so you need to run faster and faster toward extraordinarily low costs and prices. A point where phones cost less than everyday consumables. What keeps Samsung and LG in that game? Motorola and Sony Ericsson left once they hit profit warnings. Is that what it takes to drop what seems to be a loser business? I think not.

My bet is that by the end of 2012, it will be hard to find any branded phones which won’t run a smartphone OS. Demand and supply of smartphones will race each other to overwhelm portfolio logic at the largest companies. The zero (visible) cost of Android will snowball this effect. What’s even more provocative is that I believe the “others” will follow and abandon voice-oriented phones for smartphones almost immediately after the larger group.

So what have the Androids ever done for us?

I’ve long argued that the phone market should be studied as a whole because the competition is not between platforms but between smart and non-smart. Pricing is a leading indicator of what drives decision making inside vendors and it leads margin, and thence portfolio discussion. Android is expanding the market without crushing pricing. The margin expansion is what attracts more vendors and creates more demand. It’s a virtuous cycle.

In a way, this is all good news–even for Apple. A world full of smartphone users is a better addressable market for iPhones than one filled with voice products. iPhone’s traction was always in markets which had been seeded by some smartphones: the US with RIM and Europe with Symbian. Such a smartphone-soaked world will have better mobile broadband infrastructure, users with more demanding tastes and awareness of the value that a smart device can bring.

—

[1] The effect of “other” vendors not among the 8 listed is a big unknown. It’s been estimated that they now make up as much as 30% of total volumes and that they are beginning to ship significant volumes with Android. Without visibility into that part of the market, we should be cautious. However, the eight vendors sampled here are still a significant cohort and the conclusions still appear reliable.

[2] This industry had, until 2007 suffered from chronic price erosion. Each sustaining innovation drove a mild burst of pricing power but it never seemed to last. From color screens to bluetooth, to 2.5G to 3G to MMS, to cameras to music playback, each hardware advance was not enough to keep the erosion away. The tipping point seems to be the iPhone and the shift to software as the component that drives price power.

Discover more from Asymco

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.