RIM shipped 10.6 million Blackberries and 200,000 PlayBooks in the last quarter. Management noted that their sell-through was significantly higher for Blackberry (13.7 million) but seems to be very weak for PlayBook as the prior quarter saw 500k units shipped. Additional PlayBook units this quarter probably mostly went into new channels in Asia and there were no additional sales into North America or Europe.

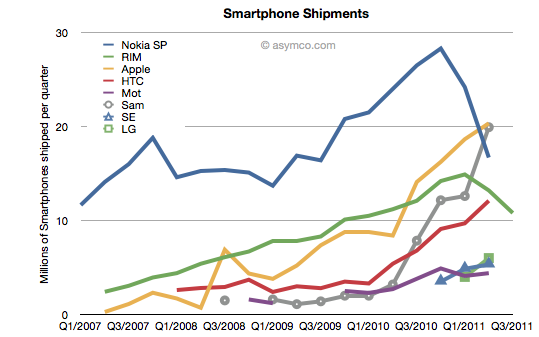

The figures for units are very poor. How poor depends on the frame of reference. Consider the shipment chart below:

In terms of the competition, 10.6 million units is less than half what Apple or Samsung sold in its prior quarter. It’s also less than what HTC sold. RIM’s volume rank will likely go to fifth place as a smartphone vendor.

In terms of its performance relative to its own history, the Blackberry volume dropped by 11% year-on-year and 18% sequentially. This is the second quarter that shipments shrank.

In terms of market share, we’ll have to wait for the competitor data over the next six weeks but the market has been growing at an average of 77% for four quarters so any continuation of this trend would imply RIM’s share dropping to single digits.

Finally, the biggest shock has been the decline in profitability. It seems that operating margin dropped from 21% to 13%. The company did incur some one-time charges for recent layoffs, but even without that charge, the margins would be around 16%. This is most alarming. The reason for such drops is that as volumes decrease fixed costs don’t decrease as rapidly or at all. The company still needs to keep sales, administration and engineering staff around and they become a larger part of the operating expenses (vs. the component costs which vary with volume of goods sold).

This effect is well understood by financial analysts and the stock price shows it with a huge drop.

But stepping back to look at the picture above, there is a clear turning point in the company. You can see the elbow in the curve for volumes whose effect is felt so deeply. What’s curious is why the pivot occurred when it did. We can point the finger to competition as the cause. But why was there no effect in the company’s fortunes when the competition actually emerged. It’s been years since the iPhone and even Android entered the market. Yet we see an impact on Nokia and RIM individually at apparently arbitrary points of time.

This is the lament of the analyst: you can clearly and accurately state what will happen but when remains a mystery. It’s the elasticity between obvious causes and their effects that makes this an inexact science or not a science at all. In retrospect, you can say that Nokia’s pivot was triggered by its public execution of Symbian, but that assumes that it was preventable–which we know is not the case. But what caused RIM’s change of growth, exactly? Why did it happen this past spring? Why didn’t the company volumes begin to decline as iPhone and Android boomed in 2009 or 2010? For quite some time RIM seemed immune to competitive pressure. We all were made fools as we called its imminent demise. Then, as Steve Jobs would say, boom!

—

Footnote:

Piecing together RIM’s performance is becoming more difficult each quarter. The data being presented is increasingly obfuscated by irrelevant detail while major information is omitted. This last management presentation was full of holes, namely:

- We have no idea of device pricing. Valiant efforts have to be made to piece together that aspect of the business. Matt Richman does a good job but it still requires some guesswork regarding PlayBook pricing to back out Blackberry pricing.

- Management detailed where Blackberries were selling-out but only detailed sell-in for the PlayBook. Obvious spin.

- They are cherry picking the data they present and each quarter it’s a different story making pattern recognition impossible.

This leads to an erosion of trust. Observers are faced with the problem of increasingly guessing what is happening each quarter. For instance, regarding pricing I prefer to include service revenues in the analysis of device sales because device+service is what is being bought by the user and vendors which can offer services as part of the device get a justifiably higher value for the product–value that I think needs to be considered as advantageous. Nokia and Apple also account for services (though not apps) as part of device sales and it makes it more convenient to compare these businesses.

Given RIM’s smokescreen, this quarter I decided to stop trying to guess Blackberry pricing and used Operating Income/Units sold as the average selling price.

Discover more from Asymco

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.