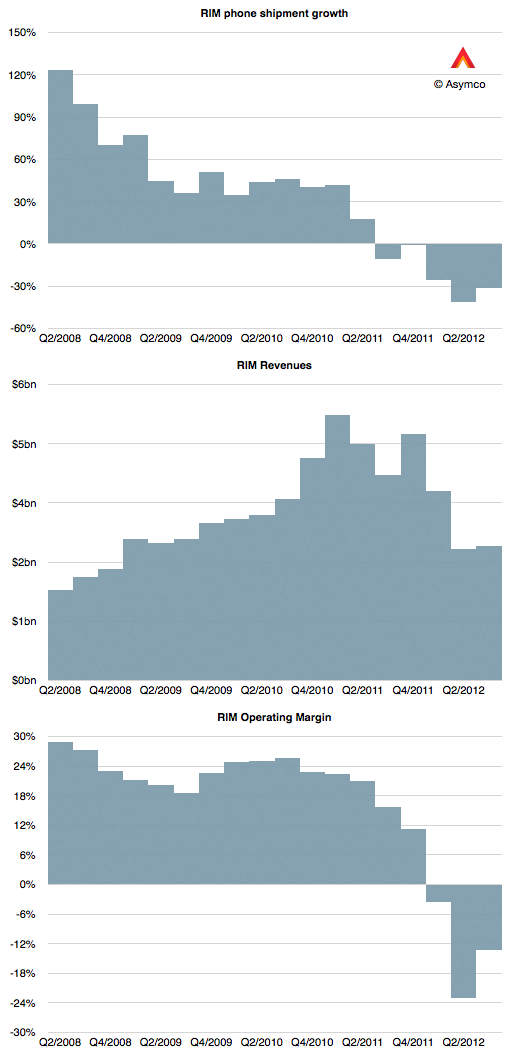

Quarterly financial data is often a lagging indicator of strategic success. RIM’s vital signs were exceptionally strong up until early 2011. Consider the following graph showing RIM’s device growth.

Using language commonly heard among analysts, one would say that the company was “reverting to the mean” and growing nearly in-line with the market. In other words, exceptional growth was over but continuing growth was likely. The company was returning to something “normal.”

However, keen observers of the market would have been hard pressed to find any reason for justifying that performance. Seen through a disruptive lens, it was evident as early as 2008 that RIM’s strategy was not sustainable. The company had a very weak smartphone product relative to emergent iOS and Android ecosystems. And yet, the company continued to prosper for nearly three years, through 2008, 2009 and 2010. Those shorting the stock during this period would have been unrewarded.

But then in early 2011 it fell off a cliff.

There was no reversion to the mean but an acceleration toward oblivion. The share price dropped to book value or below liquidation.

This pattern was very similar for Nokia. It too looked fairly strong on paper until early 2011 when it found it necessary to fling itself off a platform.

This pattern of disproportionate decline is a mirror image of the disproportionate ascent of Apple.

It might sound like a spectacular story; an anomaly, a once-in-a-lifetime reversal of fortunes. However, the moral of this story is that this is not an exceptional phenomenon. Disruption happens. It happens quickly and perhaps most quickly in this industry, and looking at trailing indicators like revenues and profits is of no help. I’ve only witnessed sharp expansions and sharp declines. I’ve never witnessed steady state, quiescent markets in technology. The history of platforms is always virtuous cycles followed by vicious declines. Whatever amplifies success seems to also amplify failure.

Rather than assuming that businesses are in a state of average growth or in some anomalous state above or below that average (from which they’ll recover) we need to think of them being either growing or failing. Going straight up or straight down.

If this is the case, how can anyone expect to manage this? Orthodox management theory assumes continuity but the world seems discontinuous.

In a discontinuous framework it’s important to look for unfair, unsustainable advantages that can be capitalized. Once exploited the advantage often disappears. The victim assumes it becomes sustainable. The survivor looks for another advantage. Resting is not an option and the mean is only an illusion.

Discover more from Asymco

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.