All phone vendors saw smartphones coming. They hired all the right market research companies and spent lavishly on analysts to confirm that phones with operating systems were imminent.

Nokia was one of the early movers, establishing its own software platforms group as early as 2002 while others like Samsung licensed Windows Mobile or PalmOS as early as 2003. Yet not much happened to sales. The number of smartphones units sold as percent of total has been fairly low.

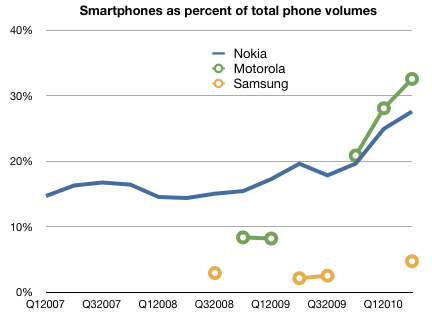

The following chart shows the number of smartphones sold as a percent of all phones sold for the top three vendors (as of the time when the chart starts early 2007). Note that the percent of smart products shipped did not accelerate or grow dramatically for the largest two vendors even into last year. It’s still a pittance at Samsung (<5%) and even less at LG.

The one vendor that did stage a shift was Motorola. (and Sony Ericsson, though later and softer) Both converts did this shift when faced with near-death experiences of sequential earnings losses and catastrophic market share collapses.

Nokia is showing signs of a secular shift to smartphones but it’s been a decade-long process so far, a slowness that ripped shareholder value to pieces.

So is the precondition for a shift to smartphone focus a collapse in the core business? It certainly seems so from the data. Motorola first, Sony Ericsson second, Nokia presently and Samsung and LG later.

Each of these decision points reflect precisely the timing of pain points with the core businesses.

Why this asymmetry? At first glance, the smartphone business should be sustaining and an attractive option to be exercised as soon as possible. It offers better margins, better prices and a better return on capital.

So why is there this disconnect? As regular readers of this blog can probably guess, my hypothesis is that the smartphone business is disruptive. Incumbents are motivated to ignore this business because it makes money in ways they cannot control. More importantly, their best customers are signaling (in non-transparent ways) that they don’t want their top vendors to participate in this market.

Discover more from Asymco

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.