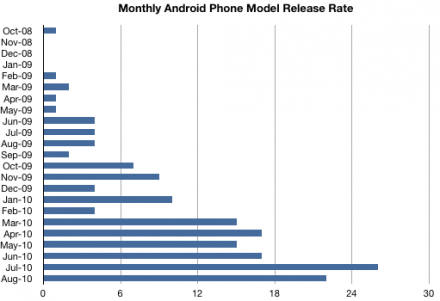

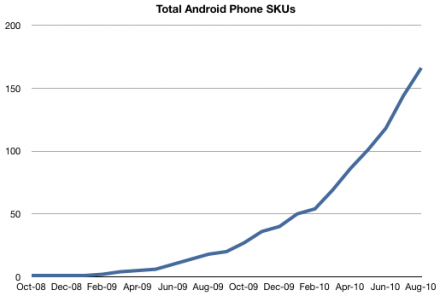

Next month will be the 24th since the first Android device launched in October 2008. The G1 was followed by another HTC device in February of 2010 and a few others in the spring. The summer of ’09 showed a steady release of up to four new phones every month. Since then the number of Android phone stock keeping units (SKUs, uniquely identifiable stockable products) increased dramatically, with the release rate increasing to 26 per month during July of this year (source: pdadb.net).

Altogether, there are have been 166 Android phone SKUs in the market with another probable 25 or so ready to launch in the next few months.

Now this may seem like a large number of different phone models in a short time, and it is, but Windows Mobile was even more proliferated as a licensed OS. At its peak over 50 new devices were released every month. The total now is over 1700 and it’s still growing.

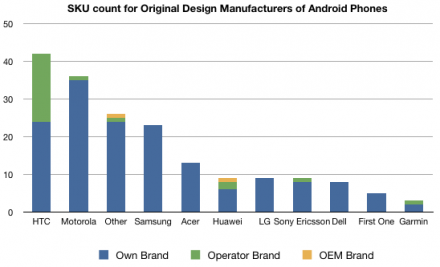

The 183 known Android devices are distributed among 10 principal vendors with another 18 minor vendors. The 18 “other” vendors (see footnote 1) have either one or two devices in the market.

The vendors or original design manufacturers list ranked by most devices follows:

I broke out the devices also by the number of operator branded devices designed by the same manufacturer (green) and any devices designed and built by one vendor but sold under a different vendor’s brand (orange). It shows how, excluding “other”, HTC is the most prolific Android builder (and seller) but also how it still depends a lot on Operator branding.

The proliferation of Android devices is indeed striking, but as I’ve pointed out before, the licensing model for Android is symmetric with that for Windows Mobile with the exception that Android is both open source and cost-free to license. This should make it highly disruptive to the paid-license model that Microsoft worked so hard to implement. It should be no surprise then that the adoption dynamics for the platform are very similar, with the same licensees that took Windows Mobile a few years ago embracing Android today.

The proliferation still has a while to go. There is production capacity for over 2000 SKUs among all the vendors in the market (especially the “other” category) and it’s only been two years since a stable version of the OS has been available. So it would not be surprising if the total number of licensed Android products will overtake the 1700 or so Windows Mobile SKUs.

So what’s the paradox?

The question that should jump out from this data is what’s the value to the participants in this, or any mobile OS licensing model? When I analyzed the Windows Mobile field in 2007 or so, it was pretty evident that very few vendors other than HTC shipped enough volumes to make a product profitable. In fact, I coined the phrase Pocket PC Paradox to describe the situation where hundreds of vendors would line up to make undifferentiated products competing for a shrinking pie. This went on first with Pocket PC PDAs, then repeated with Windows Mobile and is now repeating with Android. Nobody ever made money except for HTC, not even Microsoft.

It’s still a mystery to me why any manager would decide to make the (n+1)th Android/WinMo phone. It must be difficult to make market projections that justify the cost of developing and marketing this new product.

But here’s some help: The total number of Android phones sold through the end of last quarter was about 23 million units. The total number of SKUs launched to date then was about 118. That means that the average Android phone SKU sold 200k units (2).

Now this may seem comically low, but I will again bring up history and point out that while the WinMo bubble was in its zenith, the average Windows Mobile SKU had 50k units sold. With the SKU count increasing more rapidly than the sales rate (40% more SKUs since June) it’s very likely that the average units per SKU is dropping. So by my reckoning there’s plenty more in the Android bubble to go.

—–

(1) The “other” category includes the following vendors:

- Lenovo

- Gigabyte

- Highscreen

- Notion Ink

- WayteQ

- Forsa Posh

- Inventec

- Kyocera

- Pantech

- TechFaith

- Saygus

- Sharp

- Ziss

- Alcatel

- General Mobile

(2) I’m fully aware that the distribution of sales over the products is not even and very likely exponential, but there is no way to predict whether a given new product will be a “hero” or DOA. The dream for every manager must be that his product will be a star, but the odds get worse and worse over time and the average units sold has to be considered as including these odds.

Discover more from Asymco

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.