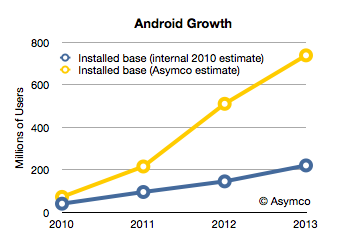

Android has had unprecedented growth. Based on activation announcements, it’s possible to estimate that thus far, about 370 million Android devices have been activated. The total number of devices in use is a lower figure which depends on replacement rate and retirement rate. This total number of devices in use at year end is estimated in the following chart.

I added the blue line which represents what Google had as an internal estimate in mid-2010.[1] The difference between the two lines shows that Android’s growth is far higher than what the company expected. If the company itself did not expect this growth, it’s unlikely anybody else did either.

Unexpected, exponential user growth is usually accompanied by a dramatic positive improvement in the finances of a company and a higher return to shareholders. The curious aspect of Android’s success is that it has not had an impact on either. The market has not “discounted” the half-billion anticipated Android users into a price for Google shares that reflects this growth. It can only imply that those users are not very valuable.

But why would there be such a disconnect between the number of users and their value?

In order to answer this question we have to come to grips with what I call “Android economics”. We need to understand how Google uses Android to make money and whether it is succeeding and if it’s not, why not.

In many ways, the Android business model is straight forward. It’s an extension of the existing Google business model: Revenue is obtained from Search, AdSense and the applications that enable these two. In the case of Android there is also revenue from app sales (Google Play a.k.a. Android Market) and from AdMob. Of course, all these revenue sources (except for Play) are sold through other mobile channels that include alternative, competing platforms. They are present on iOS, Symbian, BlackBerry and even embedded OS phones ranged directly by carriers. For each of these alternatives, Google pays for placement of their search as the default search in the browser.

To Google, total search revenue from iOS is far higher than it is from Android. That’s because iOS users engage more with their devices and there are not yet a large multiple of installed Android users vs. iOS users.

But it would make sense that having your own platform would be more economical because there would be none of these placement fees. In this sense Android is another “channel” for distribution of Search and AdSense. But one which may be a lot cheaper.

However, it turns out that it does not work that way. Android has other costs.

In fact, Android’s distribution costs might be higher than other channels. What we have to understand is that all of Google’s channel revenues have a “cost”. The revenue from a particular distributor of search results that Google generates is offset by the cost to acquire the terms. You can think of it as Google paying for the queries through a revenue sharing agreement. Google does not get search terms directly and depends on distribution. Overall, it pays about 50% of revenues back to distributors. In the case of its own web sites the rate might be lower, perhaps 40%.

Google even has a term for it: Traffic Acquisition Costs or TAC.

This revenue sharing in exchange for search terms extends to Android. Google pays about 40% TAC to Android distributors of those searches. But since Android is owned by Google, who does Google need to pay for traffic? Who is an Android distributor? Who gets the revenue share?

Google does not make a secret of it: network carriers and device vendors (OEMs) receive revenue share. From the latest earnings conference call:

Yes. I mean, again, I’m not going to talk about specific of the TAC on mobile. But as you know, we get people using our devices both organically as well as through our distribution partnerships with carriers and OEMs. And typically, the OEMs and carriers participate in some of the economics that are on the Android marketplace or Google Play and some of them participate in the economics around Google Search just the way we would do syndication on the Web platform, which you do with many partners around the world. We have similar deals on the mobile front.

– Nikesh Arora, senior vice president and chief business officer at Google Google Management Discusses Q1 2012 Results – Earnings Call Transcript – Seeking Alpha

Arora made another point in the quote above. Not only is there revenue sharing with carriers and OEMs for Search and AdSearch but also for Google Play (app and content sales.)

Device vendors and carriers get a cut. Google’s model has always been one of giving a cut of revenue to their upstream distribution. It just might be surprising to hear that device vendors like Samsung and carriers get a piece of Search and apps.

This basic observation leads to a series of questions:

- How much is paid out and to whom?

- Is that revenue sharing sustaining the ecosystem? Do vendors create Android devices and do carriers push Android to consumers because they get this revenue share or is the amount insignificant vs. device margin? What about tablets? Why haven’t Android tablets they taken off as Android phones have? Are the economics to blame?

- Is this a competitive advantage vs. other platforms? Does Windows Phone compete with revenue share for Bing? Is Microsoft offering a bigger carrot (as well as a stick?)

- How does this economic picture show up in Google’s financial and stock price performance? Or, more precisely, why doesn’t it?

- And, finally, what conditions create a virtuous cycle of growth and what conditions could turn it into a vicious cycle of decline? Is there a lurking factor which would cause Google to benefit greatly from this user base or is there an inherent point of failure in the model?

I’ll be answering these questions in a series of posts this week.

—

Notes:

- Google’s internal documents were leaked as part of the Oracle trial (Exhibit 1061). They can be found by using Google search with the following search term: “OC quarterly review”.

Discover more from Asymco

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.