Are Apple and Google competitors or are they partners?

Prior to the launch of the Android operating system, Apple and Google collaborated on many projects. Google Search was predominant on Apple products including the (at the time) new iPhone. The iPhone also launched with support for Gmail and had native Google Maps and even YouTube. Google was a cornerstone supplier for the new smartphone.

After the launch of Android only a year later, the relationship changed. The two companies came to be viewed as mortal enemies. The perception that Android was disruptive to Apple—insofar as it undercut the pricing power of the new touch-based user experience—was universal. The “zero price” of Android and its licensing by all other phone makers suggested a competitive collapse was imminent for the fledgling iPhone. Android phones were far cheaper and “good enough.” If not immediately, then with the resources of all phone makers and Google itself, Android would surely soon overtake the iPhone in performance along all dimensions. It took a great deal of courage to argue otherwise.

But, over time, the notion that the iPhone would continue to exist became more widely held. Holding on to a “premium” positioning, iPhone seemed to be have pulled a rabbit out of a hat, perhaps because of Steve Jobs’ reality distortion field or because of magical marketing. Nonetheless, doubts over long-term growth persisted.

Having survived Android, Apple was still seen as vulnerable to a multitude of Google initiatives including Chrome and Chromebooks, a range of Google Pixel phones (enabled by the acquisition of Motorola and HTC.) The entry of Google wearables (enabled by the acquisition of Fitbit), Glasses, the Play Store, YouTube content, Google productivity apps, Google cloud, Google TV, Nest, Google Assistant and numerous other services were all cited as nails in the iPhone coffin. This is all before the age of Crypto a new generation of AIs came into fashion.

Throughout this period the iPhone continued to increase its audience, growing its base of users not only from smartphone non-users but also from so-called “switchers”, that is, those who moved from Android to iOS. Apple has benefitted from this net positive switching for at least five years now as most of its addressable market has already adopted the smartphone. There are about 1.2 billion iPhone users and it’s far more likely that a new iPhone user today arrives from the 3.5 billion Android users than from the 3.2 billion people who don’t yet have any smartphone. That is because those who don’t yet have a smartphone today are also likely to not yet have access to electricity, cellular networks or money.

Indeed, it is Android that seems to be in a precarious position. The ecosystem is bleeding not just high-end users but also from fragmentation. Chinese OEMs in particular deliver their own experiences and code bases, eschewing Google services altogether. Large OEMs such as Samsung are seeking to differentiate with their own experiences and ecosystems and accessories and chafe against Google’s hardware offerings. Upgrade rates to new Android versions are poor. Support of hardware beyond a few years is lacking. But, most fundamentally, Google has not developed a business model that directly fuels development of Android.

Put simply, Android is not a profitable product. It’s not designed to create revenues. It’s designed to reduce costs.

To understand this, we have to understand Google’s business. It’s not very complicated. Google’s revenues in the last quarter are segmented as follows:

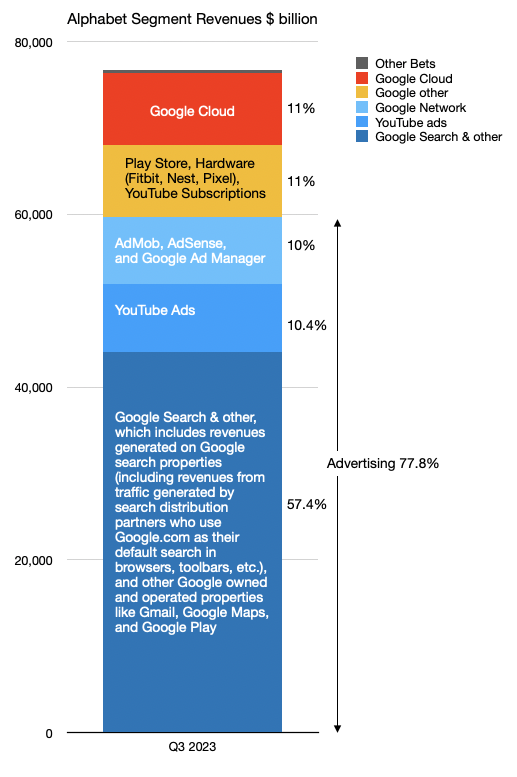

The colors above indicate the major categories. Blues are Advertising, yellow is “Other” and red is Google Cloud. Other Bets, consisting of research projects, is a 0.4% rounding error. Apart from Search which is about 60%, each major category is about 10%. Advertising as a business model is about 78%.

To Alphabet’s credit, Advertising as a business model has been reduced from 94% a few years ago. Much of that credit goes to Cloud which is a B2B business and has completely different resources, processes and priorities than Search. The “one trick pony” label is less applicable to Google today.

Search however, and the ancillary properties, are still, by far, the largest sources of revenues and profit. Note that Android itself is missing from this mix apart from Play Store which is a direct Android extension. Play does contribute somewhat as part of “Other” but the OS itself is an enabler across all these categories.

While not directly producing revenues, what Android does is perhaps even more important. It helps reduce the amount Google has to pay to access its customers. Think of Search as a system which takes queries in and puts results out. These results are what advertisers pay for and the queries are what Google pays for. The output depends on the input. That input is harvested from many users. Access to those users is not free. The cost can be paid by building access directly (Android) or by paying for access to someone else’s property (Apple, Windows, or Firefox). In old-school business terminology this is called distribution.

Distribution is often ignored or considered a superfluous “middleman” to be bypassed. But distribution is foundational to any business. It is, effectively, other people, outside your company, helping you sell your product because they have access to the customers. They get paid for that access, often with a percent of sales. Stores are distribution. Wholesalers are distribution. Resellers are distribution. Without distribution scale cannot happen. Distributors help both producers and consumers by creating access.

Access is also provided by what we call infrastructure. Just like you can’t travel by car from your house to your destination without roads, all access to products and services is effectively infrastructure. If you own the infrastructure then you have to pay to build it and maintain it. If you don’t own it you have to pay to use it. All infrastructure has value and all infrastructure has costs.

This all makes more sense when recalling the historic birth of Android. At the time (2006 to 2008) the worry for Google was that Microsoft’s mobile operating system (Windows Mobile née Windows CE) would be licensed as was Windows. That is to say that all phone OEMs would take a license for a nominal fee and build Windows Mobile phones. Microsoft would thus dominate the mobile computing market the way it dominated the PC market (with market share above 95%). Microsoft would then ensure that Bing search was the default on all devices running Windows and Windows Mobile, thus blocking access to what was expected to be the next 3 billion users while capturing all search ad dollars ad infinitum.

If Windows Mobile were to dominate, Google would be denied distribution, at any price. It would thus be relegated to, at best, 10% market share of mobile search. This would be an existential crisis.

In this setting, Apple was an ally for Google. Apple was not a search engine provider and was very welcoming of Google search on a nascent Safari browser. Whereas Explorer would block Google search, Safari would offer default placement. Not for free, but for a reasonable cost. Google was a “go-to-market” partner for Apple and it was a symbiotic relationship.

However, the expectation of Google at the time was that Apple would be no more successful with iPhone than it was with the Mac: A fringe of “creative” or “fanboy” quirky oddballs. This was not just Google’s expectation. It was everyone’s expectation.

Android was built to counter a Microsoft mobile OS monopoly with a “zero cost” option vs. Microsoft’s end-user-license model. Microsoft made money selling software. Both system software (Windows) and application software (Office.) Google would give away system software (Android) and services (Gmail and Docs) but make money on advertising.

A genius move. Phone OEMs would much rather pay zero of the OS on their phones than for the non-zero Windows Mobile license. [On a $200 retail cost phone (and thus $90 bill of materials) a $8 OS license is a huge cost.] Google’s Android did indeed block Windows Mobile from getting a foothold in the post-PC era.

But it did so by taking some short cuts. Android itself was an acquisition in 2005 (for $50 million, with a keyboard interface) and, in response to the iPhone, a new touch user interface was developed. It so happened that this interface copied as closely iOS as Windows had copied the original Mac. This perceived theft was such an affront to Steve Jobs that he declared war on Google.

It was important to ask (as few did) why did Google need to develop an OS, only to give it away. Was its business that robust if it needed to expend enormous energy and capital to build an enabler? The answer is, of course, distribution.

Google was initially not paying for distribution as most people just typed “google.com” into their browsers. As the URL field became a search field, Google could still expect PC users to make Google.com their search bookmark, one click away.

But on mobile devices, the friction of the constrained interface meant that defaults mattered. Mobile was going to require new distribution economics. Devices were going to be in the hands of many more people, who, since they did not have full-size keyboards, would type less and who would interact in new (and very succinct) ways. One click away was one click too far.

With Android (and Chrome) Google set defaults for its services across the platform. If Android was the OS then Chrome would be the default. If Chrome was the default, then Google Search would be the default. For these Android-sourced queries, Google would not pay for distribution. Or, more precisely, would only pay to build and keep Android. Thus the more Android there was, the cheaper it was to obtain search queries for Google. Google had built its own highways: it owned the infrastructure that connected users to its services. These roads were for Android users. And what about iOS users?

Over a 15 year period the smartphone went from essentially zero to 5 billion users. It became so important to those 5 billion people that they keep it with them every waking moment, use it 100 times for a total of 5 hours each day. That adds up to 182,500,000,000,000 interactions a year and, as a result, it has changed behavior, politics and humanity itself.

Throughout this period, the relationship between Google and Apple changed. From being allies, to mortal enemies to, as we shall see, partners. We have to understand this new relationship that has emerged and its consequences.

The next post will explore the relationship in detail using the lens of the deal structure that exists. A deal which is not public and largely unexamined.