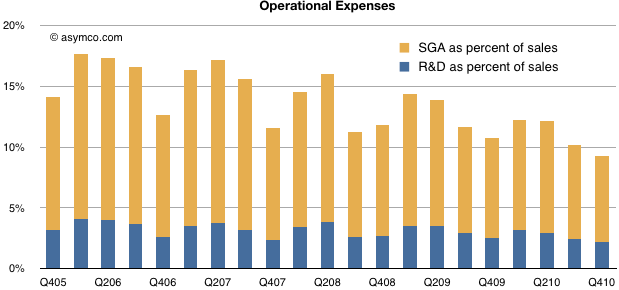

During the calendar year 2010 Apple spent nearly $2 billion in R&D. That is a significant increase from $714 million in 2006. However, as a percent of sales, R&D spending has decreased. Sales have grown more rapidly than resources hired to develop the products (or to sell them).

In Q4 2005 Operational Expenses (costs which are not tied directly to units of production–sometimes called fixed costs) were 14.2% of sales. In the last quarter of 2010, the ratio was 9.2%. Sales and administrative expenses (which include advertising, promotion and overhead) were 7.1% and R&D (which includes all engineering, testing) were 2.2%. As percent of sales both reached new lows.

The efficiency with which Apple creates sales is legendary. There can be many explanations for this but the most telling evidence of causality I can find is the small number of products in the portfolio. Tim Cook stated that given the sales value, there is more concentration of product at Apple than at any other company except perhaps an oil company. All the products Apple sells can fit on one average sized kitchen table and they generated $76 billion in sales last year.

How is this possible? First, a few words about the often misunderstood process of product development.

Most observers of technology are not aware of the pace of its development. It’s natural to assume that most R&D costs are in the product creation, or early phases of development. Coming up with something new must be hard. But that’s not actually true. Most R&D work is routine polishing of products and coordination late in the development cycle. “Productization” is far more resource intensive than “concepting”.

It stands to reason that making go/no-go decisions early in the pipeline is a lot less expensive than making stop-ship decisions prior to launch.

I have no specific evidence that this is the case, but I guess Apple conceives of plenty of concepts, but chooses to move forward to develop and market very few. Most companies don’t have the ability to decide early which products to launch and instead proceed with costly R&D and marketing in order to find out whether products will “work” in the marketplace. The proliferation of flawed products is a big cause of the inefficiency of product development.

But launching flawed products is also detrimental to brand value, something which rarely hits the books and is thus invisible to operational managers.

This uncanny ability to pick winners early in a long gestation period is my guess for why Apple is so efficient with OpEx. The question of how to develop this ability is left for another day.