I began thinking carefully about Apple in 2005 when the stock was priced at around $55/share. I remember that the events which made me consider Apple in a different light were the launch of the iPod shuffle and the launch of the Mac mini. Both moves signaled to me that the company was serious about competing with non-consumption. At that point I thought that the company was a potential opportunity as an investment.

But I also remember that many people at the time thought that the stock price was too expensive. At $50, the company was much more expensive than the year before. The stock started 2004 at about $11/share. The reason it had climbed so much was that the iPod began to be a real world-wide growth phenomenon. Buying Apple was buying into the iPod and many said the price was unsustainable given such a strong dependency on fickle consumer tastes. It was a much riskier proposition than that of competitors like Dell and HP which made product for reliable buyers like enterprises.

Indeed, by 2006, the shine was off. In the first half of 2006 the stock collapsed from $85 a share to $50, a fall of 40%. It was becoming clear that with mobile phones taking on more music playing features, the iPod was not going to be a big story for long. What’s more, Apple had just announced that they were switching to Intel for the Mac product line. Investors saw just how vulnerable the company still was and considered that the Mac brand was in jeopardy as it transitioned to becoming a Windows-friendly machine.

However, in 2007 the company’s value recovered with the introduction of the iPhone. Suddenly there was a new product to drive sales. Nobody knew by how much or how but there was a sense that the iPhone was enough to keep Apple from oblivion.

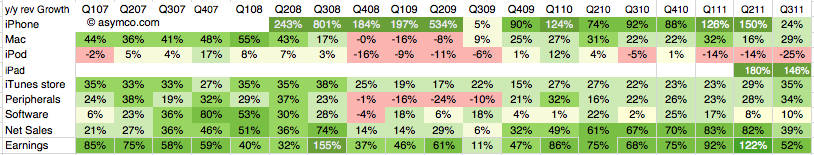

Yet, again, in early 2008 the company lost 40% of its valuation. In a rather inexplicable period following the launch of the MacBook Air, the company’s shares went into free fall. Inexplicable because the company continued to deliver solid growth with 2008 calendar quarters showing between 32% and 155% EPS growth.

Then the recession came. It caused another 40% share price collapse. Growth slowed to a range of 11% to 61% during 2009. As the marco “headwinds” blew over, by the end of 2009, with the help of a lukewarm response to the iPad, the company’s value recovered to its 2007 level. In the mean-time its earnings more than doubled.

It may not appear to be the case, but throughout this volatile period, the investment thesis remained fairly constant: Apple is a rather small collection of product bets. Owning Apple meant riding the iPod or the iPhone or the iPad as waves of growth. As soon as one growth wave was seen to start to fade, investors would say the same thing: Apple is done.

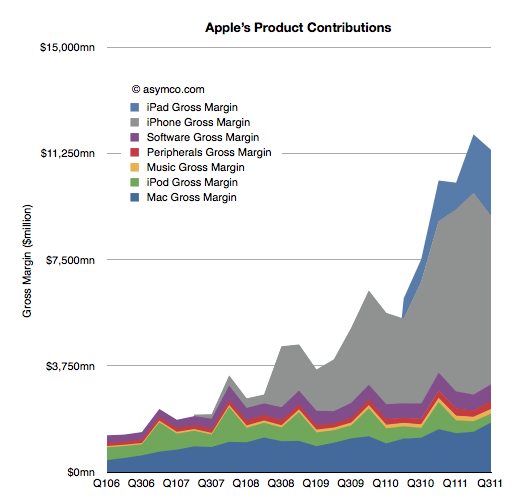

The chart below shows just what that looks like in terms of product contribution to gross margin.

The investment thesis is the same today. I’ve had dozens of conversations with fund managers and if anything, it’s even more about betting on products. The iPhone and the iPad make up such a large part of profits that the company seems to be nothing but those two things. So if there is any hint that those products might slow down, the stock is sold off.

What intrigues me about this investment thesis is not whether the signals of growth are interpreted correctly or not, but rather that an investor in Apple in 2006 was considered perfectly rational valuing Apple as an iPod company as much as an investor today is perfectly rational valuing Apple as an iPhone company. Why would anyone buy Apple for any other reason? There is no evidence that Apple can be anything more. Any fund manager positing a different point of view would surely be limiting her credibility.

The consensus is that the value of future, unknown products is zero. Not only that but the probability that there will be any products at all is equally zero. Not only that but whatever Apple does to create new products is not perceptibly valuable. The company is simply the sum-of-the-product-parts and nothing more. Cash flows from current products can easily be shown to be more than the current valuation so even these products are deeply discounted. If and when a new product shows up, it will be considered and maybe if it shows promise, the stock will reflect that, briefly.

A corollary to this investment thesis therefore is that the process of product development at Apple is worth nothing. It does not matter if the company has shown an ability to disrupt and to create new categories. The past is not a predictor. The value of the company is a discounted cash flow of current products–discounted for the odds of commoditization, which are seen to be quite high. A new hit product is a windfall, a winning lottery ticket. Something that you cannot count on.

Think about that in a different context. That’s like valuing Pixar on the box office revenues of its current movie. If Cars 2 is not beating records, Pixar is suddenly nearly worthless. The fact that Pixar repeatably creates blockbusters would be seen as meaningless. The way they built a reliable pipeline with predictable cost structures for movie-making is not interesting.

However, the fact is that Pixar did not get acquired on the basis of the last hit it made. It was acquired for its system of production. This can be confirmed not only by the price paid but by the fact that the organization was not folded into the Disney machine. It stands alone and is given autonomy. So at least in the movie making industry, predictability is seen as valuable.

So why is Apple not valued as a process company?

I think the answer lies in the lack of understanding or belief in a theory that predictable success in product development is possible. Until and unless an explanation is available that persuades a majority that Apple is as much a hit factory as Pixar then Apple without the products will intrinsically be valued at zero.

The premise of the stock market today is therefore that being innovative in technology is meaningless. Innovations are valuable but there is no such thing as an innovation process. If there was such a thing then we could measure it and put a number of its value. Until then innovation is nothing more than a spin of the roulette wheel.