What if Apple did make a car? How significant could their products be? What would it take to influence the industry’s architecture?

The global market is forecast to reach 88.6 million vehicles in 2015 and there are many ways to segment it. One could look at geography or at product configurations or the emergence of new powertrain technologies.

One could also look at the participants.

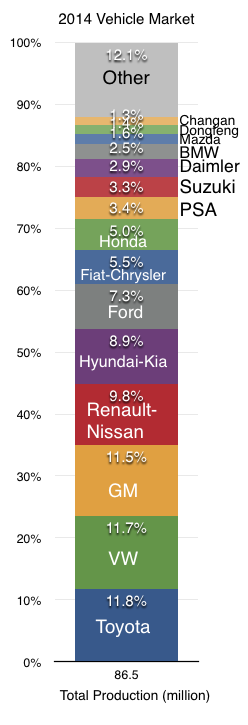

In 2014 Toyota was the top selling automaker with a total sales volume of 10.23 million vehicles. The following graph shows the leading 15 producers and the percent of total production.

One thing to note is the relative balance in market share. The top five vendors have volumes in a very similar range (9 to 12 million). Two vendors are at around 5%. Three are at 3%. To preserve this equilibrium the industry undergoes periodic merging and consolidation. Over the last half-century, there has been room for new entrants. Japanese brands entered between the 1960s and 1970s. Korean entries occurred in the 1990s and Chinese in the 2000s.

Regardless of the entries, the industry has a high degree of centralization. Ownership is often more narrowly controlled through cross-ownership and licensing. French/Japanese, US/Italian/German, Indian/German/UK cross-over ownerships indicate a globalization of financing. Indeed, only a dozen countries account for over 80% of the production (less than 10% of nations produce significant numbers of vehicles).

This structure is driven by the cost structure of volume production. The production system dictates financing and location and time constraints which underpin all deals. None of the entries (Japan, Korea, China) did much to redefine the core industry architecture (resources, processes or priorities).

So how could Apple think different?

First, the model of production could be substituted with a modular approach. This would separate the engine/body/paint/assembly plant into a deeper supplier network where components would be sourced and tooling dependence would be reduced.This speeds up ramps, reduces capital expenditure, increases flexibility, and accelerates the cadence of product evolution. Essentially, the focus would shift away from manufacturing toward design, iteration, customization and experience engineering.

Second, Apple could change the distribution model. Controlling the relationship with the end user could allow a conversation which will reveal new jobs to be done.

Third, Apple could affect the vehicle’s lifespan and hence the financing/resale and inherent brand promise of car ownership.

These are fairly obvious business innovations and they are easily foreseen.But are they enough? Would they even “move the needle”?

To break into the top 10 brands would imply a production volume of at least 2.5 million units (about the same as Daimler ships today.) At 2.65 million and a price of $55k/vehicle Apple’s revenues from cars would total about $145 billion. This is roughly the sales value of the iPhone business today. Not bad. Maybe that would satisfy a financial analyst.1

Even so, would a top 10 rank in shipments change the industry’s structure?

When I first saw the iPhone I knew that nothing would be the same after it and that Apple was poised to dominate the phone business. For the Apple car to do a similar trick in transportation the product itself has to change the perception of what a car is. Today a phone is barely something one speaks into.

Approaching the operations side of the business with a clean sheet of paper allows a fresh and rational attack on the problem. But to really make a dent in the universe Apple also needs to change the product in ways that re-define what it’s good for. And this is supposedly why Apple gets into markets. To make a meaningful contribution.

- Yeah, right. [↩]