Back from the Apple Watch event, Horace gives his trip report discussing watch pricing and what we now know of how Apple intends to sell them. What cognitive illusions might come into play as people consider the watch?

Year: 2015

Asymcar 22: The Goddess

The incomparable Citroen DS (French homophone: déesse), 60 years old this year. Hydropneumatic, self-levelling suspension aerodynamic and interior design efficiency, swiveling headlights, novel construction methods. Ahead of its time even in 1985. Why did this iconic design not endure?

We use this parable to analyze Apple Car rumors.

Peak Cable

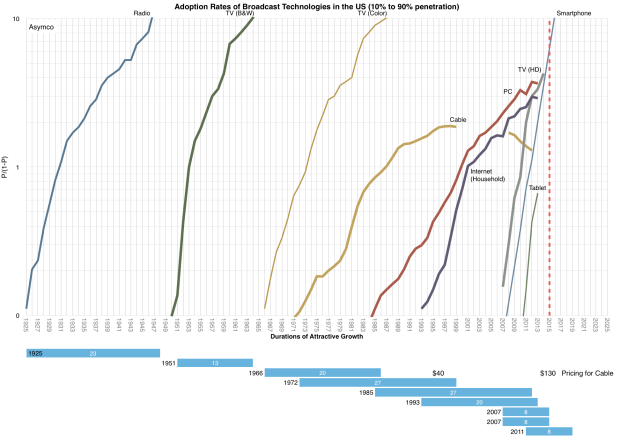

Paying for TV has been a curious consumer phenomenon. There was a time when TV was free to consumers. It was delivered as a broadcast over-the-air and paid for either by commercials (US mostly) or by taxes on viewers (Europe mostly). The consumers were delighted with the idea as it was far better than radio and radio was delightful because it was far better than no radio.

The process of convincing consumers to pay for something that used to be free was quite interesting. The first benefit to be articulated was that the quality of the picture would be much better. It would, in essence, be noise-free.1

The second benefit was an increase in the number of channels. VHF and UHF television would cover about three and 5 channels respectively while cable could offer dozens, many specializing on specific types of content like the Home Box Office (HBO) offering movies and ESPN offering sports only and MTV music videos and CNN news only.

The third benefit was fewer (or no) commercials for some of the channels. This was especially valued by fans of movies whose interruption by commercials was often detracting from the immersive value and continuity of the cinematic experience.

These benefits were very attractive during the 1980s, to the extent that about 60% of US households adopted cable. An additional group later adopted satellite-based pay-TV as the technology became reasonably cheap.

These benefits were priced modestly but as the quality and breadth of programming increased, prices rose. An average cable bill of $40/month in 1995 is $130 today2. Some of that revenue went into upgrading the capital equipment in use (the plant) and some into paying for the higher production values. Yet more went to the sports leagues and their players whose business models increasingly depended on broadcast rights.

These benefits were priced modestly but as the quality and breadth of programming increased, prices rose. An average cable bill of $40/month in 1995 is $130 today2. Some of that revenue went into upgrading the capital equipment in use (the plant) and some into paying for the higher production values. Yet more went to the sports leagues and their players whose business models increasingly depended on broadcast rights.

The Critical Path #144: The Hookup

Horace and Anders discuss Apple’s brand reorientation from the intellectual and analytical to the emotional and instinctual. Moore’s Law is fundamentally incompatible with luxury so new measures are necessary. What should one call this new paradigm?

The Critical Path #143: Moving Parts

Horace and Anders discuss the design of Gordon Murray and what it might take to enter the automotive industry. Is an integrated strategy the only way? What job would an Apple car be hired to do?

Conversations with Apple’s brand

According to Folkore, in 1981 Apple took out a two page ad in Scientific American which explained that whereas humans cannot run as fast as other animals, a human on a bicycle is the fastest species on earth.

Jobs had made the observation that a computer was “a bicycle for the mind” earlier, in 1980, at a time when the decision to purchase a computer was driven by an intellectual curiosity and justified as an improvement or assistant to the intellect. It was to make the lighten the labors of our intellect.

Apple brand at the time as an appeal to the intellect via a humanistic argument. A more emotive positioning of a tool, but a tool nonetheless. This positioning evolved throughout the 80s and 90s into an “intersection of technology and the liberal arts.”

We can see how the conversation with the potential buyer was along the lines of appealing to the intellect while offering a humanist sweetener. Humanizing the product allowed it to be accepted into a world that feared the complexity and awkwardness of such a machine.

During the 2000s, with the ascent of iPod, the conversation shifted to prioritizing the emotions more than the intellect. The products had to appeal to those who wished to express and enjoy products of emotional value. Products like music and videos and the output of the arts rather than the sciences. The brand became emotional rather than intellectual. It created an aesthetic, and become culturally iconic.

During the 2010s, with the ascent of iPhone and the emergence of the Watch, the brand speaks a language of instinct, leaving intellect and emotion as secondary or tertiary voices. Instinct is visceral, lust-inducing. It seems to short-circuit any of the rational. Non-rationalism does not mean irrational. It just skips right over the head and heart and hits the gut.

One could argue that during these three decades, the organs the brand was engaging in conversation shifted from the mind to the heart and then to the glands. Those glands which release hormones and are directed by non-rational neurons. The evidence of the conversation would be in resulting products causing pupils to dilate, breaths to be quickly drawn and skin temperatures to rise.

The brand therefore has managed to move from a rational, to a neurological, to an endocrine response.

The curious thing is that during these shifts, Apple’s entry into new biological spheres of influence has been largely unchallenged. I suspect this is because emotional or instinctive products are appealing due to their lack of rationalized value. In other words, what makes a product hormonally appealing is a lack of intellectual appeal1. Apple can enter into the world of lustful appeal while lustful brands can’t enter into functional appeal.

This is a classic asymmetry which perhaps no other brand can pull off.2

The Critical Path #142: The Great Insufficiency

Horace discusses his latest work at the Christensen Institute and considers why the educational system works the way it does. Can large scale education be modularized? In the second half of the show, Anders and Horace discuss the rumors about the possibility that Apple might be working on a car.

The Analyst’s Guide to Apple Category Entry

Understanding Apple’s intentions seems to be a popular parlor game and there are many attempts at divining intention from data and market study. These attempts at market research for answers are futile because Apple does not compete in existing markets but rather it creates new markets. For instance, the market for the Apple II could not have been assessed from research into the computing market of 1974. The intention for Apple to enter into music devices and services could not have been predicted through an analysis of MP3 player market in 2000. The iPhone was also not predicated on the market for “Internet Communicators” in 2006 or 2002 when the iPad was first contemplated.1

Instead of measuring the size of pre-existing markets, surveying the functionality of existing products, or weighing toxically financialized ratios like margins and market shares, I recall this ad (Our Signature, first seen at 2013 WWDC):

This is it

This is what mattersThe experience of a product

How it will make someone feel

Will it make life better?

Does it deserve to exist?We spend a lot of time on a few great things

Until every idea we touch

Enhances each life it touchesYou may rarely look at it

But you will always feel it

This is our signature

And it means everything

My interpretation of these lines, coupled with additional public statements can be used to create a “litmus test” for new product categories:

1. The experience of a product. Read: They will work on things to which they can make a meaningful contribution. To me this means that they will build things which require an integrated approach. As Apple is “the last integrated company standing” it means they will work on problems where the system is not good enough. This means that they will not work on problems where an individual modular component is not good enough. By system I mean, in the largest sense: production, design, distribution, sales, support and services must work in a seamless way. Systems analysis implies a broad understanding of the causes of insufficient performance along the dimensions of “experience”. The experiences are what differentiate the products (and lead to high margins) and these experiences are possible only through the control of interdependent modules.

2. Does it deserve to exist? Read: They will work on very few things. They will say no to many things. It’s still true that all of Apple’s products can fit on one table. That may not be true forever, but their product space will not grow as quickly as sales grow. This means that there is no notion of “marginal value” or portfolio theory where products are added because they can be justified as “moving the needle” or balancing demand. Rather, the few things which will be worked on will address non-consumption. Non-consumption of experiences.

3. Enhance life. Read: The things they release are inevitable even though nobody asked for them. The reason this is possible is that there are unmet and unidentified “jobs to be done” which are powerful sources of demand and whose satisfaction leads to unforeseen rewards. The problems that can be addressed are uncovered through a process of conversation with a few people. They are not uncovered through surveys or large n statistical studies. Without the ability to ask the right questions, big data only leads to big misdirection. In contrast, good taste in questions allows small n to lead to big insight. Apple’s ability for finding the right problem to solve comes from this greatness of taste in questions.

So given this litmus test, will Apple build a Car?

I believe the problem of transportation and its proxy, the automobile, provide all the requisite demand for Apple’s attention. Technical questions abound and they may still prove unsurmountable before a launch happens, but there are no doubts in my mind that this is a problem Apple would see fit to address.

Non-consumption of unmet and unarticulated jobs to be done can and should be addressed with systems solutions and new experiences.

The poetry is pretty clear on the matter.

- The market for phones was large but the iPhone pricing and features made it incompatible with any reasonable segment of it. [↩]

The Entrant’s Guide to The Automobile Industry

Like a siren, it calls.

The Auto Industry is significant. With gross revenues of over $2 trillion, production of over 66 million vehicles and growing1 it seems to be a big, juicy target. It employs 9 million people directly and 50 million indirectly and politically it must rank among the top three industries worthy of government subsidy (or interference). Indeed, in many countries–the US included–government interference makes it practically impossible for a producer to go out of business, no matter how poorly it’s managed or how untenable the market conditions.

But this might be the tell-tale sign that danger lurks. Theory suggests that incumbents going out of business is an essential indicator of industry health. Without their exit, entrants are never allowed to bring disruptive ideas to bear and innovation simply stops. Is this interference with mortality the only indication of entrant obstacles? Are things about to change? Is there pressure for innovation? Can we spot other indications of a crisis in this industry?

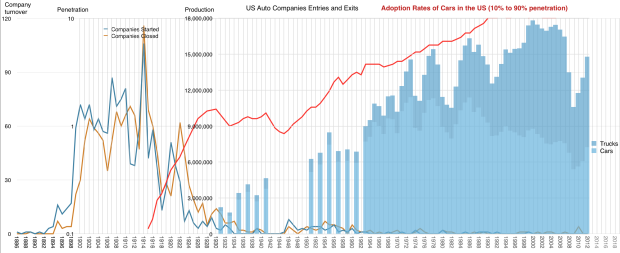

Taking the US as a proxy, here is a graph of the number of new car firm entries (and exits):

The total number of firms2 that entered the US market is 1,556. The blue line graph shows the entries and the orange line shows the exits. This sounds impressive, but note that the year when the peak of entries took place was 1914, exactly 100 years ago. Continue reading “The Entrant’s Guide to The Automobile Industry”

The Critical Path #141: Old Dogs

Horace presents the next class in The Critical MBA. Having too much of a fundamental footing could be a disadvantage when evaluating what theory might apply to a given situation. Could this be why so many fail to understand Apple? In the second half of the show, Horace and Anders discuss Amazon as retail goes online.