The iPhone is the most successful product of all time.

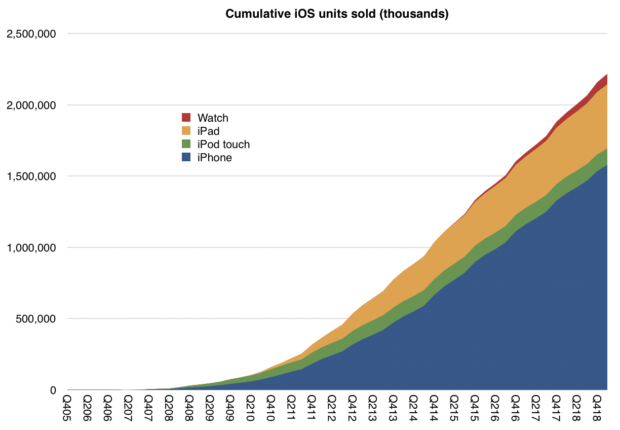

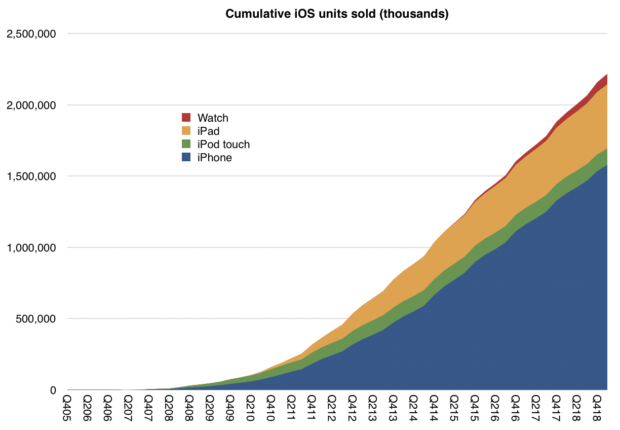

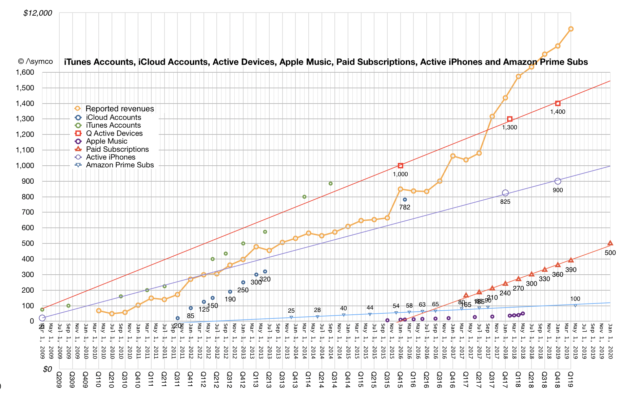

Over 1.6 billion have been sold. Including the iOS products it spun off, the total is over 2.2 billion. Of those 2.2 billion sold, 1.5 billion are still in use.

There are about 1 billion iPhone users.

Economically speaking, iPhone sales have reached one trillion dollars.

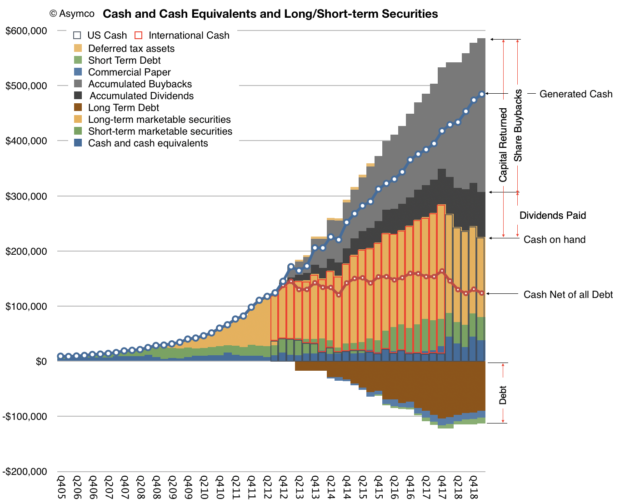

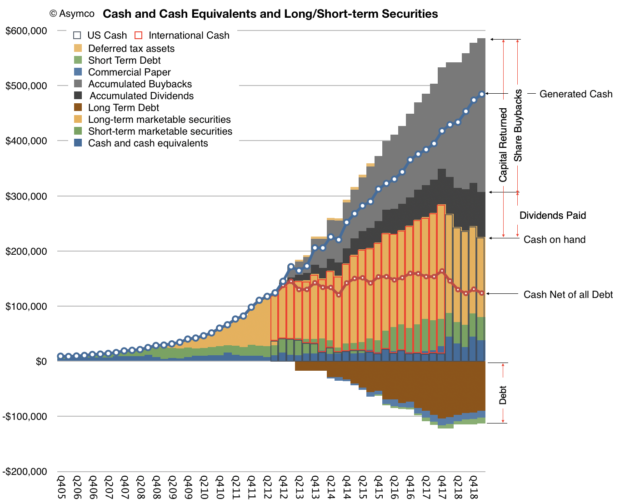

Since the iPhone launched, Apple’s sales have totaled $1.918 trillion. Of those trillions about one half a trillion was accumulated in the form of income.

Of that half trillion in income, $360 billion was paid out to shareholders. and $131 billion was paid in taxes.

This sounds like a good business, but no business is good if it is static. What makes a business great is dynamism. The idea is to constantly maneuver for a new or enhanced way of doing business as technologies enable entrepreneurs to fundamentally change how value is captured or allocated.

The iPhone story isn’t static, the “pivots” or change in direction are several:

- The App Store, a platform for collaborative innovation where millions of developers are offered the chance to improve the product.

- Accessories, a licensing model for third-party hardware that works with the iPhone

- Distribution through multiple channels

- Integration with other Apple Products

- The marketing of older products alongside new ones at reduced prices

- An expanded product portfolio with a broader range of prices

- Trade-in and financing options

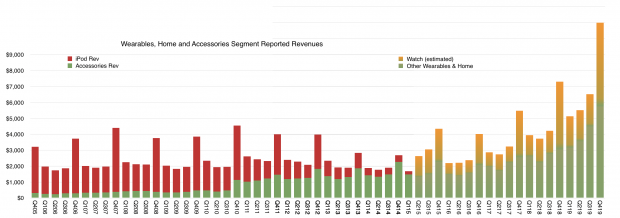

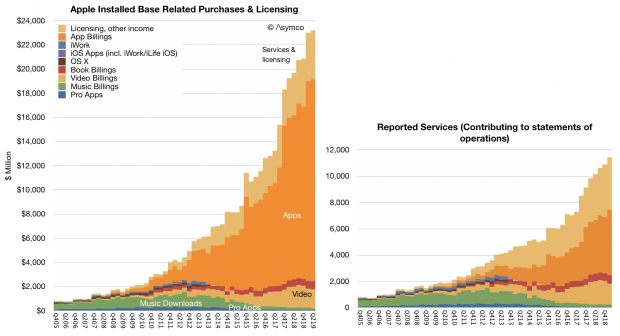

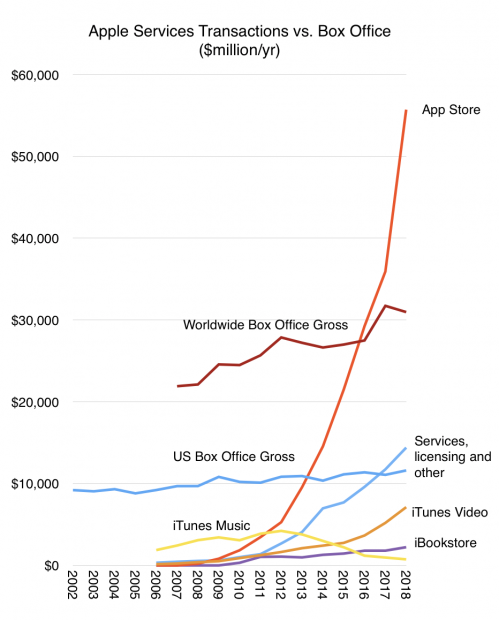

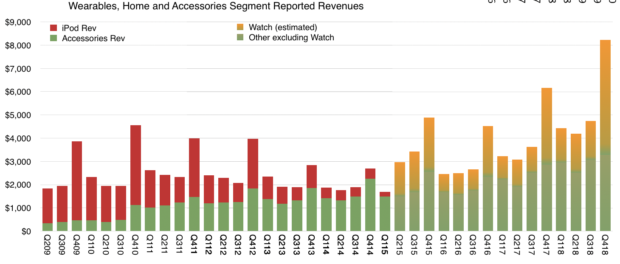

Each of these initiatives contributed to the iPhone growth story but the biggest change in business model was the addition of services. Apple Services grew out of the iTunes business that pre-dates the iPhone and was established to provide content for the iPod.

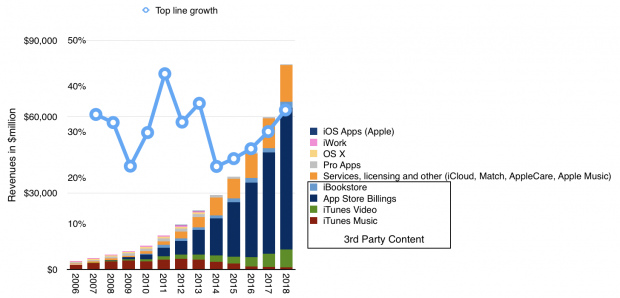

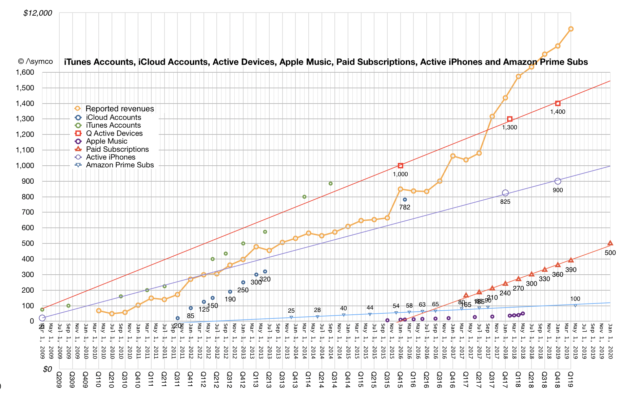

In 2006, the year before the iPhone launched, Apple customers spent $3.3 billion on iTunes, Software and Services. By 2018 the spending rate was $80.5 billion/yr. It’s very possible that this year’s spending rate will reach $100 billion/yr. This new division is simply called Services today and consists mainly of third-party apps and third-party content sales as well as licensing.

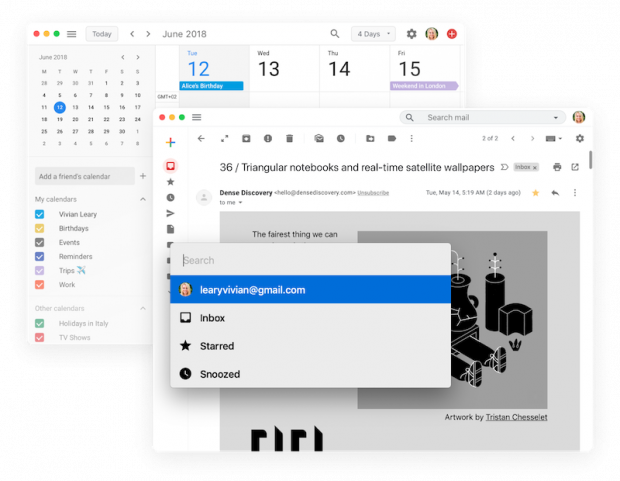

Recently Apple launched a set of new services that it will offer itself. This includes television, films, financial services and news. Apple already has a music service of its own and file storage (iCloud) both of which are offered as subscriptions.

Apps are also allowed to offer paid subscriptions, and that total has reached 390 million, growing at 30 million a quarter with an expected total of 500 million by 2020. That amounts to one subscription for every other iPhone in use.

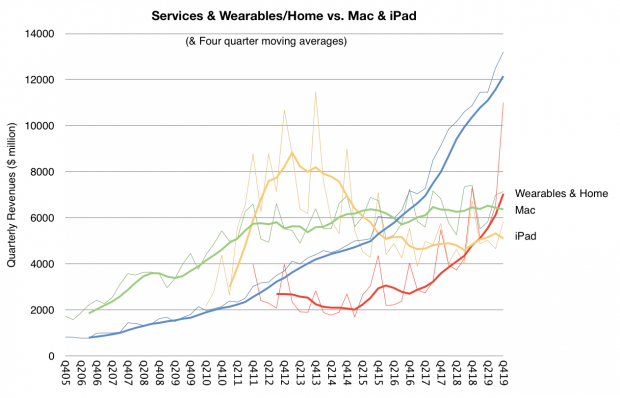

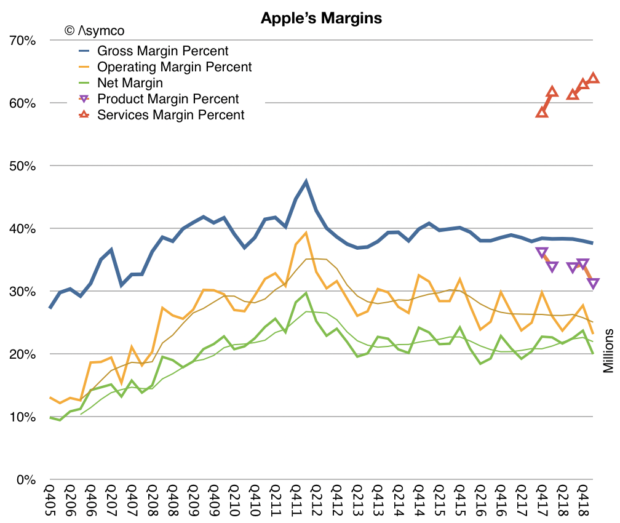

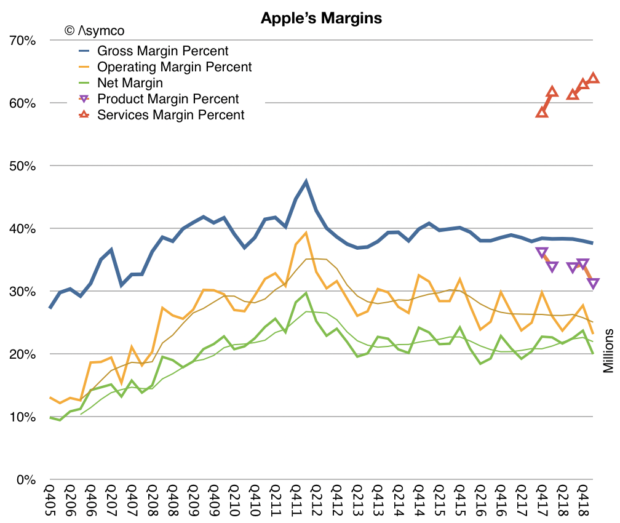

Some would argue that even with a $43 billion revenue rate, ($80 billion billing rate) Apple’s business is still a hardware business and that comes with low margins, potential for disruption, non-recurring revenues and cyclicality.

This is not the case. Apples’s business has high margins (64% gross margin for services, 34% for products), has been resilient over 12 years while attracting hundreds of imitators at lower price points, and has loyalty and satisfaction which results in more than 90% re-purchase rates. Cyclicality is driven by seasonality and product lifespans, not competition.

This common misconception of Apple is why it continues to be valued at a deep discount to not only peer companies who are services oriented (Google, Facebook, Microsoft and Amazon) but also at a discount to the overall market (the S&P 500).

Apple, since its inception, has always been oriented around its customers, not its products. The questions asked by management are “what can the company do to deliver experiences and satisfaction” rather than “what products can the company build”.

Every company is bound by its capabilities but the best companies re-shape these bounds because they are defined by priorities.

A priorities-driven company habitually re-designs its processes and its resources. A resources- or process-driven company re-designs its priorities as its capabilities change.

Moving as it does between computers, devices, software, services, retail, logistics and manufacturing means that it’s not classifiable as an “x” company where “x” is an industry sector. Rather, the company should be classified by the set of problems it seeks to solve (e.g. communications, community, productivity, creativity, wellbeing).

This disconnect between what people think Apple sells and what Apple builds is as perplexing as the cognitive disconnect between what companies sell and what customers buy.

Companies sell objects or activities that they can make or engage in but customers buy solutions to problems. It’s easy to be fooled that these are interchangeable.

Conversely Apple offers solutions to problems that are viewed, classified, weighed and measured as objects or activities by external observers. Again, it’s easy to be fooled that these are the same.

This analysis is, of course, applicable to any company. Here I’m using Apple as a lens. This is because it’s just so much easier to tell this story with the narratives and anti-narratives that are so widely disseminated.