On a future filled with autonomous Winnebagos.

Author: Horace Dediu

Why does Apple TV deserve to exist?

Since writing Peak Cable six months ago, surveys, research and analysis have contributed to the themes of unbundling the TV package. The data under scrutiny is, as usual, the data that can be gathered. Unfortunately the data that can’t be gathered is where the insight into what is happening may lie. For instance, what matters for an entertainer is not how much you’re watched but how much you’re loved. Measuring love is done poorly with data on payment for subscriptions.

A better proxy might be time. Liam Boluk makes the point in his post that “focusing on cord cutting or even cord shaving largely misses the point.” Don’t follow the dollars, he says, follow the time or engagement. “Relevance” is what matters.

His data shows how linear TV has fallen by roughly 30% among the young (12-34) in the last five years. The trouble for the TV bundle (and advertisers) is that this is the most culturally influential group. They are also the group which will grow into the highest income group over the next decade. And this group does not love TV.

We have to remember that it was the youth who drove early radio, TV and consumer electronics markets. Those young are now the old which still cling to the old media, served by companies that grew old with them. They are the “high-end” customers with which Nielsen itself has grown. They have the most money to spend and they are the targets for the ads1

Paying $150/month to watch incontinence and erectile dysfunction ads—at a time not of your choosing—is preposterous for the young. They may like the programs but not the way they are packaged, delivered or interrupted. They are not smarter than their parents. They, like their parents, took to new technology more quickly. What makes the technology new is also what lets its makers separate the content from its delivery. These new technologies allow “modularizing” or unbundling that which was was integrated/bundled and thus allow their developers to focus on the customer’s real jobs-to-be-done.

Unsurprisingly, incumbents have responded by throttling access to original programming–an asset over which they still exert influence as distributors. Netflix and Amazon are taking the path of responding with their own blockbuster productions. Although Silicon Valley has more capital to deploy than Hollywood this battle of attrition is by no means one that incumbents will win, and generally, it’s not going to be pretty.

Tweaking the nose of the incumbent might not be the way to establish asymmetry. The better tactic may be to help the system survive but offer a “short-term alternative”. This is how iTunes took on and won Music. When Napster and file sharing created a clear and present danger to the industry, Apple’s approach of a controlled alternative allowed the industry to finally move to a digital download model.

Continue reading “Why does Apple TV deserve to exist?”

- no longer the Pepsi generation, they are the Depend and Viagra and pharmaceuticals generation [↩]

The Critical Path #162: Nerd Culture

We welcome Henri Dediu for an advance look at technology and the world from the point of view of the latest generation. Insights from this unique perspective and your questions on this special episode of The Critical Path.

Source: The Critical Path #162

Ep. 27 – Horace Dediu on The Disruptive Nature of Apple TV and Apple Car by The Eric Jackson Podcast

Eric spoke with Horace Dediu about how disruptive the new Apple TV will actually be, the nature of the media landscape, how Apple could draw viewers away over time, and the potential for live events and interactive apps. We also explore what would make a new car from Apple disruptive and why Apple didnt just buy Tesla.

Asymcar 25: Cars Online, The Selfie Experience with Mathew Desmond of Capgemini

Mathew Desmond of Capgemini joins us to discuss Cars Online 2015: “The Selfie Experience, The evolving power of the connected customer.”

We begin with the finding that “One-half of customers are interested in buying a car from a tech company like Apple or Google. This is true even of customers who are satisfied with their current brand and dealer experience. It is particularly true of young customers (65%) and those in growth markets (China: 74%; India: 81%).”

Backing up a bit, we discuss the automaker’s dilemma, that is the legacy manufacturing, distribution and support infrastructure and contrast that with the “clean slate” approach an entrant might enjoy.

The concept and inherent conflicts of a “Master Customer Record” fuels a deeper dive into “Continuity”, the buyer’s desire for a seamless experience.

Finally, we reflect on the perils that may lie ahead as the auto ecosystem attempts to improve the retail experience.

Listen via Asymcar.

The Modularity Revolution. How markets are created

My presentation at Aalto University in Helsinki on The Modular Revolution. This is what you get if you give me a whole hour to talk.

Soft Underbelly

Executives at car companies have suddenly had to answer questions about potential entrants into their business. This is a big change. I don’t recall a time when this was necessary for over 30 years. For decades the questions have been about labor relations, health care costs, regulation, recalls and competition from other car makers. To ask questions about facing challengers posing existential questions must seem terribly impertinent.

For this reason, Bob Lutz, in his dismissal of Apple’s entry, is not alone. The industry has a century of history and has seen little disruption in the classic sense. I wrote a long piece on the fundamentals of the industry titled “The Entrant’s Guide to the Automobile Industry” which explained why this industry has been so resistant to disruptive change. At best a massive effort over multiple decades usually leads in a small shift in market share.

However, one should read that post as a thinly veiled threat. Just because disruption seems hard does not mean it isn’t possible. Indeed, the better you understand the industry the more easily you can observe its vulnerability and the more rigid the industry seems the more vulnerable it may be to dramatic change.

The formula for successful entry is the same for all industries: compete asymmetrically. This means introduce products which change the basis of competition and deter competitive responses by making your goals dissimilar from those of the incumbents. This is classic “ju-jitsu” of disruptive competition.

Here’s how it would work.

Bob Lutz suggests that there is no profit to be gained from selling cars on the premise that costs are very high while pricing will be held down by competition. That may be true but entrants could deploy new processes that lower the costs of production. Traditional car making is capital intensive due to the processes and materials used. There are however alternatives on the shelf. iStream from Gordon Murray Design proposed switching to tubular frames and low cost composites. BMW has an approach using carbon fiber and other composites. 3D printing is waiting in the wings. All offer a departure from sheet metal stamping.

With new materials, costs for new plants can be reduced by as much as 80% and since amortizing the tooling is as much as 40% of the cost of a new car, the margins on new production methods could result in significant boosts in margin.

There is a downside however. What is usually compromised when using these new methods is volume and scale of production. So that becomes the real question: how many cars can Apple target? 10k, 50k, 100k per year? Could they target 500k? That would be 10 times Tesla’s current volumes but only a bit more than the output of the Mini brand.

Now consider that the total market is 85 million vehicles per year. For Apple to get 10% share would imply 8.5 million cars a year, a feat that is hard to contemplate right now with any of the new production systems. On the other hand selling 80 million iPhones and iPads in a single quarter has become routine for Apple and that was considered orders of magnitude beyond what they could deliver. Amazing what 8 years of production ramping can offer.

So the answer to the operating margin might be in a combination of new processes and new ramp strategies.

But there are more levers of change. Continue reading “Soft Underbelly”

How quickly will ads disappear from the Internet?

I was always bemused by the notion that the Internet was able to exist solely because most users did not know they could install an ad blocker. Like removing Flash, using an Ad blocker was a rebellious act but one which paid off only for early adopters. But like all good ideas, it seemed obvious that this idea would spread.

What we never know is how quickly diffusion happens. I’ve observed “no-brainer” technologies or ideas lie unadopted for decades, languishing in perpetual indifference and suddenly, with no apparent cause, flip into ubiquity and inevitability at a vicious rate of adoption.

Watching this phenomenon for most of my life, I developed a theory of causation. This theory is that for adoption to accelerate there has to be a combination of conformability to the adopter’s manifest needs (the pull) combined with a concerted collaboration of producers to promote the solution (the push). Absent either pull or push, adoption of even the brightest and most self-evident ideas drags on.

Ad blocking offers a real-time example of this phenomenon. On desktop or even laptop computers ads were tolerable and the steps required to naviagate in order to implement effective1 blocking were non-trivial. In addition, no platform vendors were keen to promote products which hindered revenues for their most important ecosystem partners.

Ad blocking as an activity had neither the pull nor the push.

Continue reading “How quickly will ads disappear from the Internet?”

- By effective I mean a combination of whitelists and customizations [↩]

Apple Assurance

Apple is categorized as a vendor of consumer electronics. More specifically, a member of the “Electronic Equipment” industry in the “Consumer Goods” sector. If indeed this is what it’s thought to be selling, there is a problem because it isn’t what its customers are buying.

Apple’s customers buy a mix of hardware, software and services under a brand that assures a certain quality of experience. This bundling and integration of otherwise disparate things is why the brand is such a success.

This anomaly between what Apple is thought to sell and what buyers actually buy can leave the casual observer confused. As a result the company’s categorization as vendor of hardware deeply discounts its shares. It is, in other words a less valuable business. This is because a seller of consumer electronics does not benefit from “system valuation” since there is minimal loyalty to the product after the sale.

The consumer electronics vendor has no network to leverage, no ecosystem adding value after the sale, no platform and works through multiple levels of distribution to reach the customer. In contrast, a system vendor can expect benefits from network effects, ecosystems, and a coveted relationship with the end user.

The result is that the valuation of a consumer electronics vendor is based on the momentum of individual products. Apple has always been valued this way. Each hit product is considered to be a stroke of luck/genius and the chances of recurring are discounted to about zero. Regardless of the fact that it has a track record of “home runs”, Apple’s hit rate is not considered sustainable.1. Certainly Apple is not valued as being able to generate reliably recurring revenues.

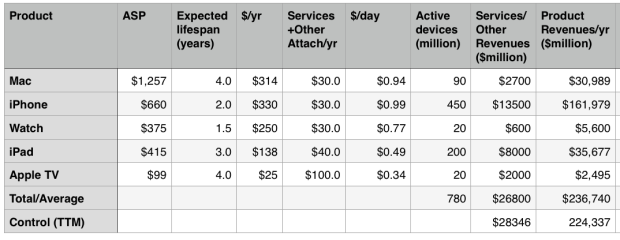

But what if we were to value Apple on the basis of what people are buying rather than what it’s thought to be selling?

The model is simple enough: determine the number of users, estimate the lifespan of the products, and figure out the services attached to the products; then, given the price, obtain a price per product per day. You then can get a recurring revenue figure.

I did just that and the results are in the following table:

Continue reading “Apple Assurance”

- The P/E ratio is the primary indicator in this analysis [↩]

Asymcar 24: Get rid of the Model T men

Should organizations hire people with industry skills and experience or capable, driven outsiders?

Horace shares tales from Henry Ford’s personnel practices during the Model T to Model A transition.

A discussion of aesthetics and jobs to be done. Tesla’s development, supply chain, aesthetics and market position while contrasting that with Toyota’s introduction of the Prius.

We close with speculation on what a “meaningful contribution” to the auto ecosystem might look like.