I recently tweeted that any discussion related to wearable technology needs to begin with a description of the job it would be hired to do. Without a reason for building a product, you are building it simply because you can.

The reason a product deserves to exist is that it can do a job that needs doing and that few, if any others can also do it. This happens when the job is unstated and difficult to perceive. Put another way, the difficulty behind jobs-to-be-done based design is that jobs are never plainly evident. In contradiction to invention, where the problem being solved must be as clearly stated as its solution, value-creating innovation meets new and unarticulated needs. Even when created, the value is more subtly perceived, often only after prolonged use.

Which brings me to the M7. Apple chose to highlight a component (curious in itself) which it bills as a “motion coprocessor”. It claims to be measuring motion data via accelerometer, compass and gyroscope and processing the information in some way. By bundling the sensors and their management into one integrated chip battery consumption is reduced and these motion monitoring functions are performed more efficiently.

But what for? The examples given during the presentation for an iPhone with M7 don’t add up to a lot of benefit. An iPhone could be used as a fitness companion but it would not a very good one. Compared with, for example, a Nike FuelBand, an iPhone could not track your activity well. It’s often not moving, sitting on a desk or in a purse or pocket while you are doing exercise. It’s too big to take into a basketball game. It can’t “observe” your activity because it’s not worn during many activities and if it is worn it is in a position which does not inform much about what you’re doing. Phones are too big to be used as physical activity monitors.

Hence the question of what is the M7’s job to be done. As part of an iPhone, it does not seem to have one. Saving a bit of battery life is not a job, and certainly not one that needs to have billing in a media special event. The answer must be that the M7 was developed for some other, as yet unstated reason.

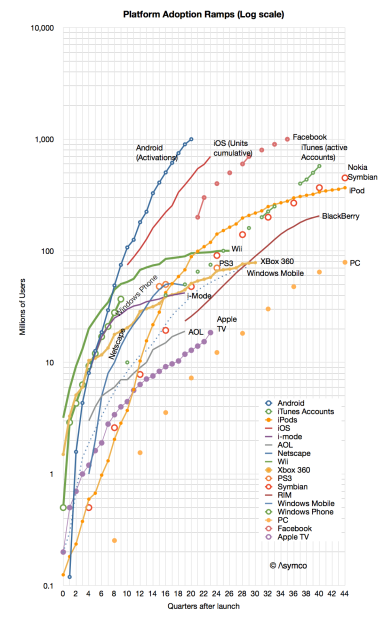

When the A series chips were created Apple leveraged the in-house design and cost reduction to make a wide range of products with more than 700 million examples built. Designing a chip needs a broad application domain.

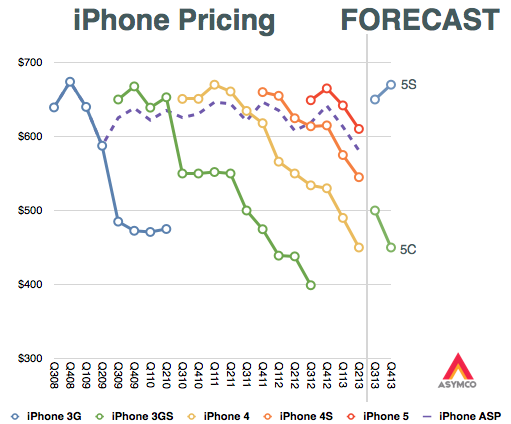

Perhaps this is why Apple chose to describe the iPhone 5s as “forward-thinking”. The M7 and the Touch ID are like research projects whose actual value will be realized at some future time, in probably different contexts. The M series of chips may become Apple’s “low end” microprocessor as the A series climbs the trajectory into core computing tasks (read: phone, tablets, TV, laptops).

M might be the chip for the wearable segment, woven into a whole new fabric of uses and jobs to be done.