Analyst Jeffrey Fidacaro with Susquehanna Financial Group in a note to investors:

- Apple to build 3 million CDMA iPhones in December

- That would put total GSM and CDMA iPhone production for the quarter at between 21 million and 22 million.

- For the current quarter, Apple is set to build between 18.2 million and 18.4 million GSM-only iPhones.

- Expects Apple to sell a record 11.6 million iPhones in the fourth quarter of the company’s fiscal 2010. 39 percent q/q increase[1][see UPDATE below]

- As for the iPad, suppliers were said to have plans to build 7 million units for the current quarter, a 56 percent increase from the previous three-month frame.

- Expects Apple to ship 4.75 million units into the current quarter, 45 percent growth q/q, to a total of 13.4 million units in calendar 2010.

via AppleInsider | Suppliers say Apple will build first 3M CDMA iPhones in December.

What I don’t get from these numbers:

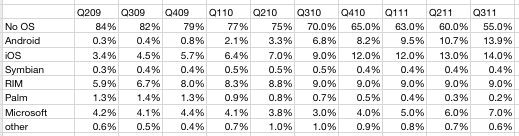

- current quarter production: 18.2 million

- current quarter units sold: 11.6 million

- inventory at end of Q: 6.6 m units [I am assuming minimal inventory at start as iPhone 4 was just launched]

- next quarter production: 21 million

- next quarter units sold: ?

- inventory at start + production = 27.6 million

My own estimate is for more than 12 (and up to 13) million units will be sold this quarter. I think inventory of more than half of production is too high for Apple. They usually carry only about 10% inventory.

My December quarter units sold may need revision but now stand at 14 million. If I substitute 14 million in the “?” above then the inventory at end of December would be 13.6 million which would be nearly 100% of units sold–clearly unacceptable. Either production is too high or sales are too low.

I am at 4.7 million iPads for the quarter an 13.9 million for the year. No major difference in opinion.

—

[1] This forecast for 39% growth would make this quarter the second lowest growth quarter for the product. This makes is hard to believe because every launch quarter has usually been breaking records for growth. The 3G launch saw 516% growth and the 3GS saw 644%. To see 39% for the iPhone 4 makes me wonder especially as the comparable year ago quarter was not a launch quarter so growth should be off a low base. Last quarter, when the iPhone 4 was leaked and the channel was drained the product had 61% growth.

Compare also to the Mac which had 33% growth last quarter. Are we to believe that launch quarter iPhone growth is barely higher than Mac growth?

The figure of 11.6 million is also in-line with other analysts which seems to indicate another forecasting failure for the cohort.

[UPDATE] I checked the figures and 11.6 million iPhones is equivalent to 58% growth y/y. The (now corrected) article was citing q/q growth. However, 58% growth is still the second lowest growth quarter for the product.