IN a recent release, Apple reported that “more than 90% of stores in the US, 85% of stores in the UK, and 99% of stores in Australia accept Apple Pay.” This is encouraging but a very small view for the global Apple Pay picture. How can we assess where Apple Pay is and how do we even measure success? My expectation six years ago was that Apple Pay would be a “$1 billion business” by 2020. Now that 2020 has ended, how was my six year prediction?

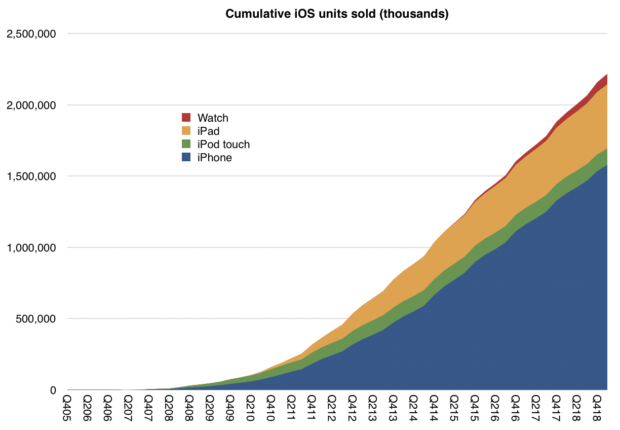

I always recommend counting customers rather than (or before) dollars so let’s begin with that. According to one source Apple pay users worldwide reached 507 million by September 2020. This is about 50% of iPhone users and therefore a decent adoption rate (starting as it did six years ago.) The data shows a growth rate of about 66 million in 2020 but a deceleration from 150 million the previous year. This data is obtained through surveys as there is no reporting from any participants.

There is a smattering of other samples about transaction volumes, mostly behind pay walls, but the overall story of adoption is typical: an s-curve where we are either at the point of inflection or slightly after it. If we are half-way then perhaps saturation will occur in another six years.

More concerning is the distribution of these users. A lot of the data that is collected on mobile and online payments (and mobile wallets) is US only. Historically the US was a good place to measure technology adoption as the US was usually the leader. The automobile, PC and many other consumer technologies saw their market defined by the US.

But not so much anymore. The digital mobile phone broke the rule. Today mobile payments is breaking it again. Note that although the iPhone is over-represented in the US (as share of all phones) Apple Pay point-of-sale support is under-represented in the US.

According to one survey, in mid 2018, there were an estimated 38 million Apple Pay users within the United States, and 215 million outside (5.5 times more!) Outside the US mobile payments are nearly 100% accepted by default but in the US the support is patchy and characterized by active intervention to deny.

I’ve used Apple Pay everywhere in Europe without friction. From vending machines to highway tolls to drive-throughs, public transit and parking meters. I can recall one failure to do so in the last six months (a state-owned gas station).

The same cannot be said of the US. Where at WalMart and Home Depot there is the capability of support but an incomprehensible refusal to do so. One rumor about why Home Depot denies it is because they were hacked once and are paranoid about any technology. Walmart may be spiteful due to margin/cost, valuing a few basis points over customer satisfaction, convenience, hygiene and employee productivity. These holdouts are the laggards. Perhaps there is some pride in denying their customers a basic convenience but there certainly isn’t profit in it.

It gets even weirder when it comes to banks. In the US almost all banks immediately supported Apple Pay as an extension of their bank cards. In Europe the banks became the holdouts, rolling out support slowly and perversely.

So when you consider the dependencies of Apple Pay:

- Sufficient number of users with iPhones/Watches (check)

- Support from Banks (great in US, spotty outside)

- Willingness of retailers to accept (sluggish in US, perfect outside)

- Availability of points-of-sale equipment (universal by now

It’s an impressive achievement.

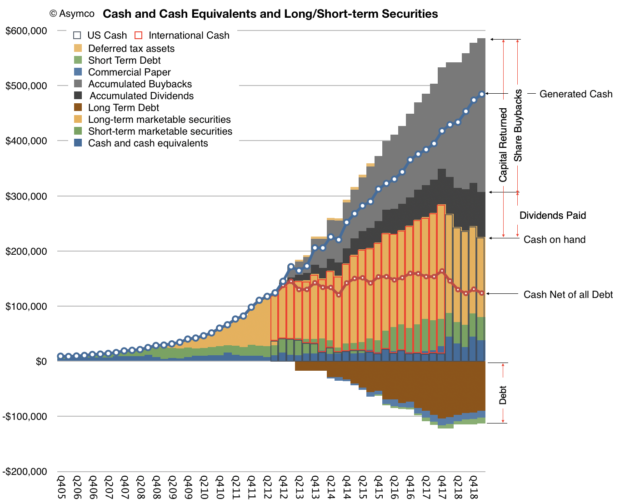

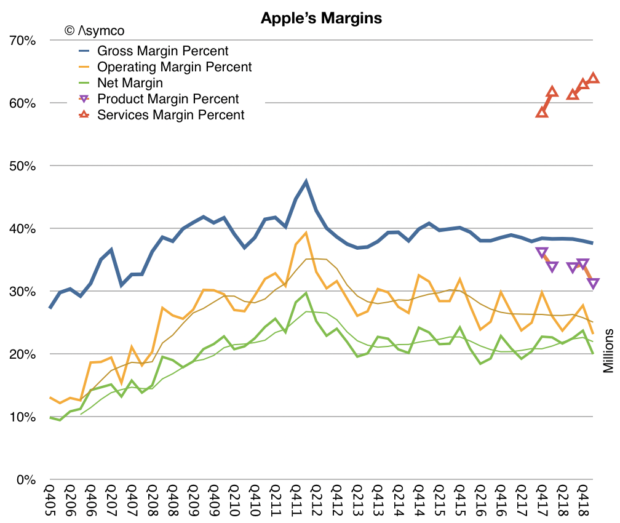

My expectation six years ago was that Apple Pay would be a “$1 billion business” by 2020. This was based on a take rate of 15 basis points ($15/$10,000 in transactional value). Juniper Research, which regularly examines payment transaction markets, now expects that Apple will see global Apple Pay transactions of $686 billion by 2024.

At that 15 basis point rate it amounts to $1.03 billion. Thus this particular research suggests that I was off by 4 years, making the $1 billion pay day a 10 year target rather than six.

But maybe that is no fault of Apple’s. The transaction volume is also equivalent to 52% of the proximity mobile payment market. Half the addressable payment market is a pretty good market share for a company holding 25% of the smartphone user base.