In the “Race to a Billion” there is a graph showing Android reported activations and iOS cumulative unit sales alongside cumulative console sales. The contrast between mobile phone platforms and game consoles is striking, with an order of magnitude difference in consumption. The best performing console to date is the Wii with about 100 million units sold so far.

[UPDATE: Thanks to Danny Nemer cumulative sales of Sony’s PlayStation 2 (using production shipments from FY 2000-05 and recorded sales for FY 06-12) is 155.81 million units]

However, that is an incomplete picture of the game platform business primarily because consoles are not the entirety of the business. Mobile (but dedicated) gaming platforms have been sold for some time.

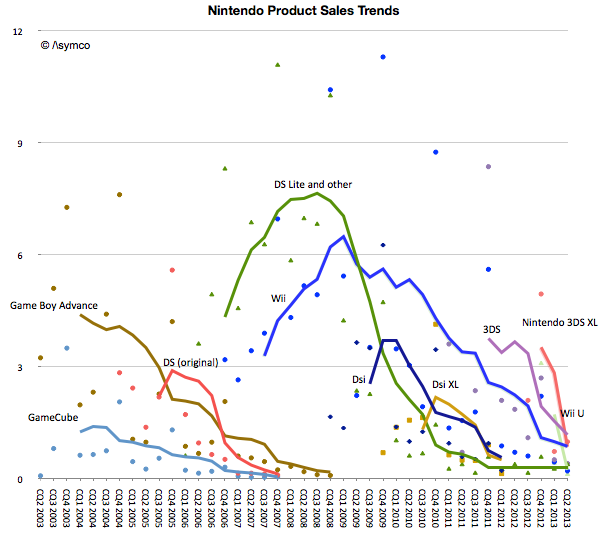

To give a better picture of the game business we prepared the following graphs. The first shows Nintendo’s product lines with actual unit shipments (shown as colored dots in millions of units per quarter) and the trend (shown as trailing twelve months’ average trend lines).

Note that fixed and mobile products are both shown on the same graph. The picture that emerges is that for Nintendo, its mobile platforms combined are more popular than its fixed consoles with a total of 186 million mobile devices sold since 2003.

There is also a pattern of generational change. The GBA, DS and GameCube era was superseded by the DS Lite, DSi, Wii era. The Wii era (or generation) was significantly more popular than the GameCube generation. If there is a problem however, it seems to be that the new generation devices or consoles are not forming a new era. The Wii U and 3DS are not growing nearly to the level of the previous generations and have faded quickly.

To summarize, the unit volume graph for Nintendo is below.1 Continue reading “Game over”

- This is a smoothed graph showing what sales would have been if they had been evenly spread out over a 12 month period. The actual sales would total to the same area but would be much more seasonal and thus noisy. [↩]