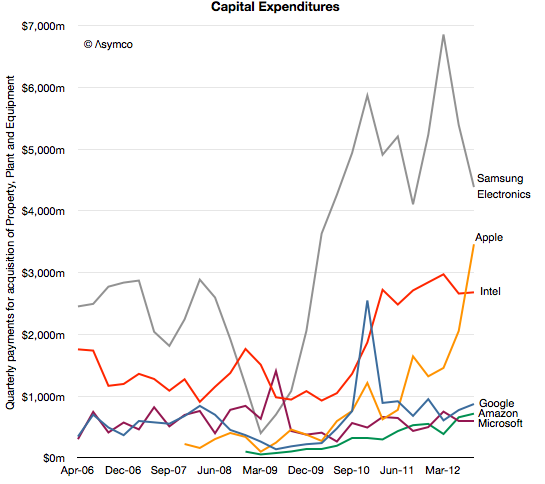

Having described the Revenue, Operating Margin and cost structure for Samsung Electronics it’s time to review their investment strategy.

The Economist summarized it well:

[Samsung’s] businesses look remarkably disparate, but they share a need for big capital investments and the capacity to scale manufacture up very quickly, talents the company has exploited methodically in the past.

Samsung’s successes come from spotting areas that are small but growing fast. Ideally the area should also be capital-intensive, making it harder for rivals to keep up. Samsung tiptoes into the technology to get familiar with it, then waits for its moment. It was when liquid-crystal displays grew to 40 inches in 2001 that Samsung took the dive and turned them into televisions. In flash memory, Samsung piled in when new technology made it possible to put a whole gigabyte on a chip.

When it pounces, the company floods the sector with cash. Moving into very high volume production as fast as possible not only gives it a price advantage over established firms, but also makes it a key customer for equipment makers. Those relationships help it stay on the leading edge from then on.

The strategy is shrewd. By buying technology rather than building it, Samsung assumes execution risk not innovation risk. It wins as a “fast follower”, slipstreaming in the wake of pioneers at a much larger scale of production. The heavy investment has in the past played to its ability to tap cheap financing from a banking sector that is friendly to big companies, thanks to implicit government guarantees much complained about by rivals elsewhere.

Can we find evidence of this capital intensity?

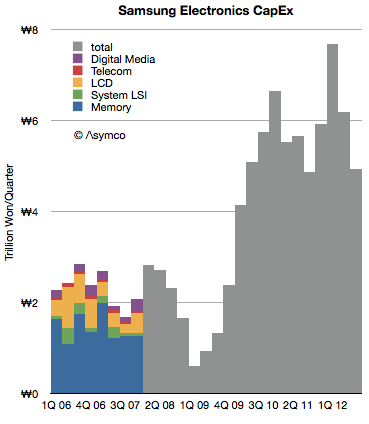

To answer, I reviewed Samsung Electronics CapEx as reported in their quarterly cash flow statements. The following graph illustrates the data:

Note that during 2006 and 2007 the company specified expenditures on an operating divisional level. Since 2008 it has reported only a total. For the years where divisional detail is available, the percent split looks as follows. Continue reading “Samsung's Capital Structure”